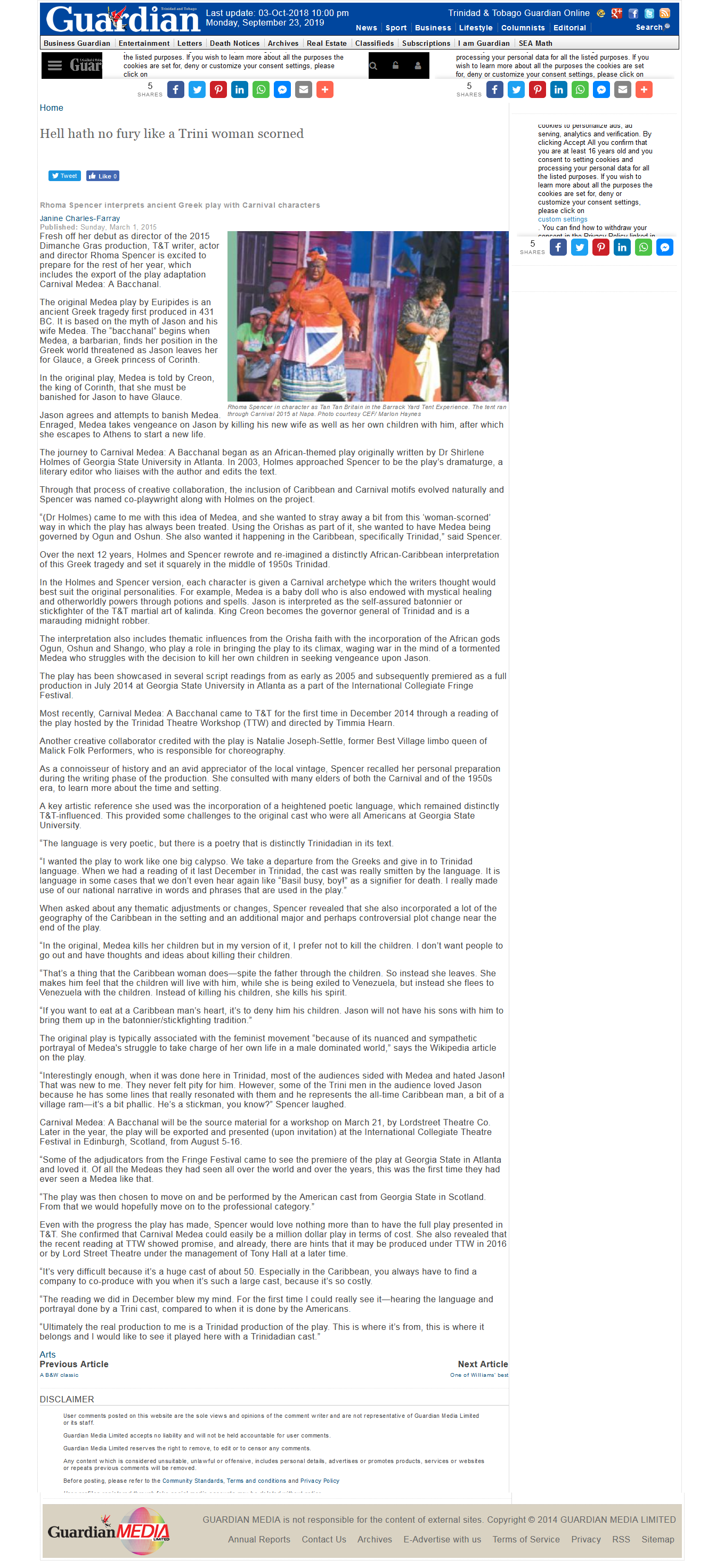

Fresh off her debut as director of the 2015 Dimanche Gras production, T&T writer, actor and director Rhoma Spencer is excited to prepare for the rest of her year, which includes the export of the play adaptation Carnival Medea: A Bacchanal.

The original Medea play by Euripides is an ancient Greek tragedy first produced in 431 BC. It is based on the myth of Jason and his wife Medea. The “bacchanal” begins when Medea, a barbarian, finds her position in the Greek world threatened as Jason leaves her for Glauce, a Greek princess of Corinth.

In the original play, Medea is told by Creon, the king of Corinth, that she must be banished for Jason to have Glauce.

Jason agrees and attempts to banish Medea. Enraged, Medea takes vengeance on Jason by killing his new wife as well as her own children with him, after which she escapes to Athens to start a new life. The journey to Carnival Medea: A Bacchanal began as an African-themed play originally written by Dr Shirlene Holmes of Georgia State University in Atlanta. In 2003, Holmes approached Spencer to be the play’s dramaturge, a literary editor who liaises with the author and edits the text.

Through that process of creative collaboration, the inclusion of Caribbean and Carnival motifs evolved naturally and Spencer was named co-playwright along with Holmes on the project.

“(Dr Holmes) came to me with this idea of Medea, and she wanted to stray away a bit from this ‘woman-scorned’ way in which the play has always been treated. Using the Orishas as part of it, she wanted to have Medea being governed by Ogun and Oshun. She also wanted it happening in the Caribbean, specifically Trinidad,” said Spencer.

Over the next 12 years, Holmes and Spencer rewrote and re-imagined a distinctly African-Caribbean interpretation of this Greek tragedy and set it squarely in the middle of 1950s Trinidad.

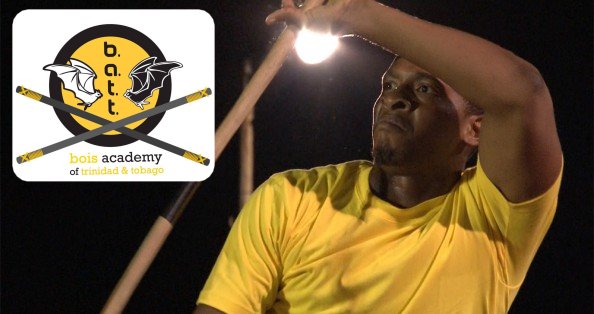

In the Holmes and Spencer version, each character is given a Carnival archetype which the writers thought would best suit the original personalities. For example, Medea is a baby doll who is also endowed with mystical healing and otherworldly powers through potions and spells. Jason is interpreted as the self-assured batonnier or stickfighter of the T&T martial art of kalinda. King Creon becomes the governor general of Trinidad and is a marauding midnight robber.

The interpretation also includes thematic influences from the Orisha faith with the incorporation of the African gods Ogun, Oshun and Shango, who play a role in bringing the play to its climax, waging war in the mind of a tormented Medea who struggles with the decision to kill her own children in seeking vengeance upon Jason.

The play has been showcased in several script readings from as early as 2005 and subsequently premiered as a full production in July 2014 at Georgia State University in Atlanta as a part of the International Collegiate Fringe Festival.

Most recently, Carnival Medea: A Bacchanal came to T&T for the first time in December 2014 through a reading of the play hosted by the Trinidad Theatre Workshop (TTW) and directed by Timmia Hearn.

Another creative collaborator credited with the play is Natalie Joseph-Settle, former Best Village limbo queen of Malick Folk Performers, who is responsible for choreography.

As a connoisseur of history and an avid appreciator of the local vintage, Spencer recalled her personal preparation during the writing phase of the production. She consulted with many elders of both the Carnival and of the 1950s era, to learn more about the time and setting.

A key artistic reference she used was the incorporation of a heightened poetic language, which remained distinctly T&T-influenced. This provided some challenges to the original cast who were all Americans at Georgia State University.

“The language is very poetic, but there is a poetry that is distinctly Trinidadian in its text.

“I wanted the play to work like one big calypso. We take a departure from the Greeks and give in to Trinidad language. When we had a reading of it last December in Trinidad, the cast was really smitten by the language. It is language in some cases that we don’t even hear again like “Basil busy, boy!” as a signifier for death. I really made use of our national narrative in words and phrases that are used in the play.”

When asked about any thematic adjustments or changes, Spencer revealed that she also incorporated a lot of the geography of the Caribbean in the setting and an additional major and perhaps controversial plot change near the end of the play.

“In the original, Medea kills her children but in my version of it, I prefer not to kill the children. I don’t want people to go out and have thoughts and ideas about killing their children.

“That’s a thing that the Caribbean woman does–spite the father through the children. So instead she leaves. She makes him feel that the children will live with him, while she is being exiled to Venezuela, but instead she flees to Venezuela with the children. Instead of killing his children, she kills his spirit.

“If you want to eat at a Caribbean man’s heart, it’s to deny him his children. Jason will not have his sons with him to bring them up in the batonnier/stickfighting tradition.”

The original play is typically associated with the feminist movement “because of its nuanced and sympathetic portrayal of Medea’s struggle to take charge of her own life in a male dominated world,” says the Wikipedia article on the play.

“Interestingly enough, when it was done here in Trinidad, most of the audiences sided with Medea and hated Jason! That was new to me. They never felt pity for him. However, some of the Trini men in the audience loved Jason because he has some lines that really resonated with them and he represents the all-time Caribbean man, a bit of a village ram–it’s a bit phallic. He’s a stickman, you know?” Spencer laughed.

Carnival Medea: A Bacchanal will be the source material for a workshop on March 21, by Lordstreet Theatre Co. Later in the year, the play will be exported and presented (upon invitation) at the International Collegiate Theatre Festival in Edinburgh, Scotland, from August 5-16.

“Some of the adjudicators from the Fringe Festival came to see the premiere of the play at Georgia State in Atlanta and loved it. Of all the Medeas they had seen all over the world and over the years, this was the first time they had ever seen a Medea like that.

“The play was then chosen to move on and be performed by the American cast from Georgia State in Scotland. From that we would hopefully move on to the professional category.”

Even with the progress the play has made, Spencer would love nothing more than to have the full play presented in T&T. She confirmed that Carnival Medea could easily be a million dollar play in terms of cost. She also revealed that the recent reading at TTW showed promise, and already, there are hints that it may be produced under TTW in 2016 or by Lord Street Theatre under the management of Tony Hall at a later time.

“It’s very difficult because it’s a huge cast of about 50. Especially in the Caribbean, you always have to find a company to co-produce with you when it’s such a large cast, because it’s so costly.

“The reading we did in December blew my mind. For the first time I could really see it–hearing the language and portrayal done by a Trini cast, compared to when it is done by the Americans.

“Ultimately the real production to me is a Trinidad production of the play. This is where it’s from, this is where it belongs and I would like to see it played here with a Trinidadian cast.”